Debates

Learn about the leadership of African-American legislators in the struggle to pass the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and the continuing effort to eradicate discriminatory housing policies and practices.

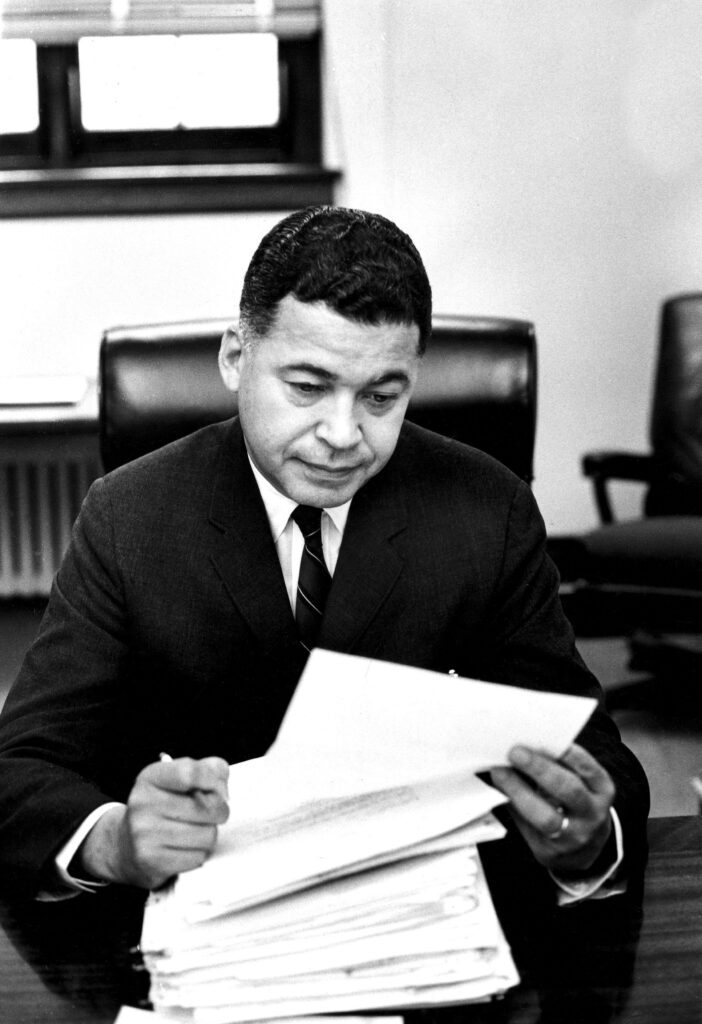

Sen. Edward Brooke and President Lyndon Johnson Meet in the Oval Office

Shortly after becoming the first African American to serve in the U.S. Senate in nearly a century, Sen. Edward Brooke of Massachusetts met with President Lyndon B. Johnson in the Oval Office. The next year the two men would work to pass fair housing legislation.

African-American members of Congress have proved strong voices in support of fair housing legislation in the ongoing and contentious debate over the issue in Congress. In the two decades leading up to the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, African-American legislators regularly called for Congressional action to end housing segregation. During this period, Representative Adam Clayton Powell (NY) was an outspoken critic on the House floor of both discrimination in public housing projects and Federal Housing Administration lending practices that promoted redlining.

In the early 1960s, African-American members of Congress, including Representatives Powell and Robert Nix (PA), continued to demand passage of meaningful civil rights legislation to address housing inequality. In November 1962, President Kennedy issued Executive Order 11063, directing all Federal agencies which administered housing programs to prevent discrimination. This order prohibited discrimination in federally funded or subsidized housing. Senator Edward Brooke (MA) argued from the floor that though the order represented progress, it was not sufficient to overcome the accumulated effects of many years of racial discrimination in housing. Sen. Brooke stressed that with the majority of the nation’s housing in private hands, the order failed to attack housing where the nation lived.

Debate intensified as the growing open housing movement and urban unrest throughout the country brought the issue of fair housing to public attention. Between 1966 and 1967, fair housing supporters in Congress regularly called upon their colleagues to fulfill their moral responsibility to the nation by passing legislation to end discrimination in all its forms, including housing. Opponents asserted such legislation would rob Americans of their basic right to private property as well as the right of an owner to decide to whom to sell or rent that property.

Those opposed to fair housing legislation in both 1966 and 1967 worked to defeat proposed bills by introducing amendments to weaken enforcement provisions or exempt large portions of the housing market from the prohibition against discrimination. Frustrated by these amendments, Representative William Dawson (IL) spoke out from the House floor, arguing that preventing discrimination in the sale and rental of single-family dwellings was the most important part of the proposed fair housing legislation:

“In its present form, this title would exempt about two-thirds of our existing housing. It would exempt most of the housing in our Nation’s suburbs. It would mean that some 20 million Americans would continue to be ghettoized in the slums of our cities. Such a limited attack on segregated housing will do less than needs to be done for the desperate housing needs of our Nation’s Negro people. It will do little to stem the growing racial stratification of our major cities and the growing community unrest which results from the degraded housing in their slum cores.” (112 Congressional Record p. 17772, August 1, 1966).

In 1968, Senators Walter Mondale (MN) and Edward Brooke (MA) jointly authored a fair housing amendment to introduce as part of the larger Civil Rights Act of 1968. Debate over the bill was heated. Sen. Brooke took the floor several times to defend and call for passage of the amendment. “Fair housing is not a political issue, except as we make it by the nature of our debate,” he chided Senate colleagues, “[i]t is purely and simply a matter of equal justice for all Americans” (114 Congressional Record p. 2279, February 6, 1968). Those opposed to fair housing legislation argued it was not the federal government’s place to infringe on individual’s rights by forcing neighborhood integration. Sen. Brooke responded: “Fair Housing legislation has been labeled ‘forced’ housing. I believe that true ‘forced’ housing is exactly that situation the ghetto dwellers find themselves – trapped in the slums because they can go nowhere else” (114 Congressional Record, p. 2280, February 6, 1968). Ultimately, Congress chose to side with Sen. Brooke and passed the legislation President Johnson would sign into law as the Fair Housing Act in April of 1968.

A few years later, Congress began consideration of a number of amendments to the Fair Housing Act. In the late 1970s, debate focused on the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) enforcement powers. Representative Shirley Chisholm (NY) shared the CBC’s support for the use of administrative law judges in fair housing cases during a hearing before the House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional Rights of the Judiciary Committee on the proposed Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1979:

“It can be safely assumed that critics of broadening administrative powers for HUD, many of whom are critics because they fear increased compliance activity, will voice their concerns couched in arguments about the growth of bureaucracy and the taxpayers’ burden. I would point out to these critics that American society is presently paying for the costs of housing segregation … We must ask ourselves why, in lieu of the fact that some 16 Federal agencies presently have cease and desist authority, that the Secretary of HUD has been without such powers for the 11 years since passage of Title VIII? In effect, we have been indicating during that time that housing discrimination is a matter of secondary national importance” (125 Congressional Record, p. 17341, June 29, 1979).

Both the House and the Senate held multi-day hearings on the proposed legislation during which time members of the full Judiciary Committee, which included Representative John Conyers (MI-13), refined the legislation. The resulting 1980 Fair Housing Amendments Act passed the House. Opposition in the Senate, however, filibustered the bill and introduced more than 100 amendments thus killing the bill in the Senate.

It took until 1988 for another bill strengthening the Fair Housing Act to make it to the floor for debate. With a compromise worked out in committee hearings, the bill garnered few negative statements on the floor from either party. CBC members including Representatives Conyers, Cardiss Collins (IL), Louis Stokes (OH), Kweisi Mfume (MD), Major Owens (NY), and Charles Rangel (NY-13), lauded the amendments both for supporting stronger enforcement and adding disability and familial status to the list of classes protected from housing discrimination. Rep. Conyers, who sponsored the original Fair Housing Act in 1968, remarked:

“I am very, very thrilled now, 20 years later … that we now come to a point in time where I think Dr. King would be very pleased about this legislation, to see that we have brought realtors and Republicans and civil rights leaders all together to say enough of the one embarrassing scourge that has made this Nation’s civil rights declarations empty for many, many millions of Americans, and that is the inability for them to live or rent in the places that they choose” (134 Congressional Record, p. 15664, June 22, 1988).

Debate over fair housing issues dropped off sharply following the passage of the 1988 Fair Housing Amendments Act. Not willing to let Congress think housing discrimination had disappeared, however, the CBC continued bringing the issue to floor. CBC members introduced and supported resolutions commemorating Fair Housing Month and fair housing legislation anniversaries. The Caucus used these commemorative opportunities to outline the history of the Fair Housing Act from the floor and call attention to continuing instances of housing discrimination. They also argued to maintain and increase funding for fair housing enforcement including the Fair Housing Initiatives Program (FHIP) and Fair Housing Assistance Program (FHAP). In 2005, for example, Representatives Al Green (TX-09), Barbara Lee (CA-13), and Alcee Hastings (FL-20) spoke out in support of their amendment to the 2005 Transportation, Treasury, the Judiciary, and Housing and Urban Development (HUD) appropriation bill. Their amendment called for restoration of funding previously cut by the George W. Bush Administration to these two fair housing enforcement programs. Rep. Green pointed out that “when it comes to housing, we cannot claim justice for all of us as long as there is injustice against any one of us. We ought to restore this funding” (134 Congressional Record, p. H5417, June 29, 2005).

In the 2000s, the CBC participated in debate over a new manifestation of discrimination in housing, predatory lending. Led by Representative Stephanie Tubbs Jones (OH), then chair of both the CBC and the Caucus’ Housing Task Force, CBC members underscored the disproportionate effect subprime and predatory lending practices on minority communities as well as the potential impact of these financial issues on the broader economy. To commemorate the 40th anniversary of the Fair Housing Act and the 20th anniversary of the Fair Housing Amendments Act in 2008, CBC members devoted time on the House floor to discussion of the importance of fair lending as a fair housing issue.