History

Learn about the leadership of African-American legislators in the struggle to pass the Fair Housing Act of 1968 and the continuing effort to eradicate discriminatory housing policies and practices.

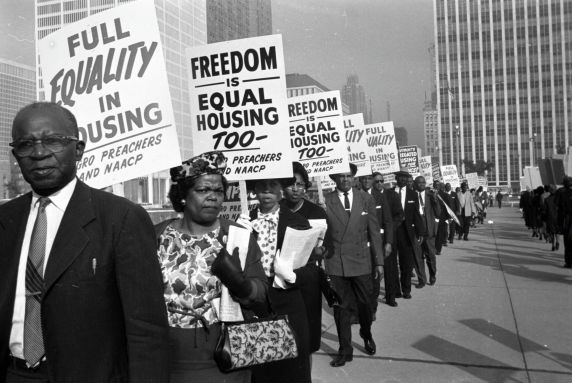

NAACP Members Picket Outside Cobo Hall in Detroit (1963)

Members and supporters of the NAACP picket outside of the Open Occupancy Hearing at Cobo Hall, Detroit, Michigan.

The need for federal fair housing legislation evolved out of a long history of discriminatory housing practices in the United States. For much of the past century, the nation existed as a racially segregated society in which black and white citizens occupied separate and vastly unequal neighborhoods. Personal prejudice, business practices, and government policies at all levels promoted and maintained residential divisions. African-American members of Congress have long understood the serious consequences of neighborhood segregation and fought to pass legislation ensuring the nation’s residents have the right to the housing of their choice.

In the early decades of the 20th century, thousands of African Americans moved north. They left behind homes in the rural South to seek jobs in rapidly industrializing Northern cities like Chicago, New York, Detroit, and Cleveland. As the Great Migration continued, local governments, white landlords, and real estate agents responded to growing numbers of black residents by adopting strategies to create racially segregated neighborhoods. Through zoning laws, racially restrictive covenants, intimidation, and violence, whites maintained well-defined boundaries between white and black residential communities. The federal government soon joined in the effort by introducing redlining in its loan programs. Deeming African-American or mixed-race neighborhoods of high mortgage risk, the federal government refused to back mortgages in these neighborhoods. Private lending institutions followed suit. This further restricted housing choice for African Americans.

Changes in the years following World War II strengthened boundaries of residential segregation. The expansion of the federal highway system and movement of manufacturing jobs to facilities outside cities shifted economic focus away from urban centers. In addition, proliferation of low-interest loans available to white borrowers lured white families to the suburbs. This shift in residential color lines transformed the nation’s cities into inner cores of predominantly African-American residents ringed by white suburbs. Institutionalized discrimination in lending and real estate blocked African Americans from joining the exodus from city centers or from obtaining funds to improve their current homes. It also limited African Americans’ access to suburban schools, jobs, and other resources. Urban decay followed. State and local governments, supported by federal housing and development programs, attempted to improve inner city neighborhoods tearing down and rebuilding substandard housing. These efforts were far from successful, however. Much of the housing torn down was never replaced leaving many residents, the majority of them African American, with fewer housing options. Additionally, many of the public housing projects built to accommodate those displaced were located in poor, racially segregated neighborhoods. Instead of moving to areas of new opportunity, many found they were simply moved to another, similar neighborhood.

The push for fair housing, or open housing as it was known in the 1960s, arose in response to these changes in residential landscape. Bolstered by early civil rights victories like the Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, civil rights groups continued their work for equality by protesting the lack of economic resources, jobs, adequate housing, education, and public services in Northern cities.

In 1966, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference joined local civil rights leaders in Chicago for a major nonviolent protest campaign against institutionalized housing discrimination. King’s association with the Chicago Open Housing Movement helped shift national attention to civil rights struggles in the North. It also raised the issue of housing discrimination to national attention. At the same time, riots in urban centers across the country imbued the issue with a sense of urgency.

In response to these growing pressures, President Lyndon B. Johnson asked Congress to consider fair housing legislation in both 1966 and 1967. Debate on the Hill was heated during these years. Supporters argued that housing discrimination violated the country’s basic ideal of justice and was the root of a myriad of other inequalities. Those opposed to fair housing laws contended such legislation infringed on private property rights. For many Congress members previously willing to permit desegregation of the workplace and public accommodations, the prospect of integrating neighborhoods seemed a step too far. Supporters of fair housing legislation, including the seven African Americans in Congress at the time, failed to secure a strong enough majority to pass a fair housing bill.

Senators Walter Mondale (MN) and Edward W. Brooke (MA), then the lone African American in the Senate, tackled the issue again in the early winter of 1968. The two Senators coauthored a fair housing amendment and introduced it as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, a larger bill to provide protections for civil rights workers. Failure looked imminent for this attempt as well, until two events motivated Congressional action. The first was the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorder’s release of its landmark report, commonly called the Kerner Commission Report, in February of 1968. In the report, Sen. Brooke and the other members of the 11-person Commission identified residential segregation as one of the central inequalities which prompted the widespread urban disorders, or riots, which shocked the country in 1967. The report became a best-seller and was often cited in Congressional fair housing debates.

The other event which motivated Congress to pass the Fair Housing Act was a national tragedy. On April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated as he stood on a hotel balcony in Memphis, Tennessee. King’s death shocked the nation. A new wave of riots gripped the nation’s cities, including Washington, DC. As smoke from the burning neighborhoods drifted over the nation’s capital, President Johnson urged Congress to respond by passing the Fair Housing Act as a tribute to the slain leader. Days later, Congress obliged. President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, including Title VIII or the Fair Housing Act, into law on April 11, 1968 as Sen. Brooke and other fair housing supporters looked on.

The Fair Housing Act as passed in 1968 prohibited discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of housing on the basis of race, color, religion, or national origin. It also directed the Secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to oversee enforcement of the Act. Passing the Fair Housing Act was a great civil rights achievement, but required several compromises that restricted and weakened the bill. Over time, it became clear the law’s limited enforcement provisions lacked the strength to combat deeply-entrenched discrimination in the housing market. Residential segregation rates remained high and discriminatory practices persisted.

Since 1968, African-American members of Congress have played a leading role in the legislative effort to strengthen the Fair Housing Act by expanding protections and enforcement provisions. The Congressional Black Caucus regularly included amending the Fair Housing Act on its list of legislative priorities in the 1970s and 1980s. The CBC supported a successful amendment to the massive Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 to add sex to the list of classes protected under federal fair housing law. In April 1979, Representatives Parren Mitchell (MD) and William Gray III (PA), and Delegate Walter Fauntroy (DC) founded the Congressional Black Caucus Housing Braintrust and convened its first meeting in Washington, DC. Braintrust participants identified fair housing as an important legislative priority and argued in support of a vigorous campaign to amend the Act throughout the 1980s. During this time, CBC members also participated in committee hearings on housing discrimination, pressured the White House to take action, and spoke out on the issue in both the press and from the floor of Congress. Despite the efforts of the CBC and other fair housing supporters, it took until 1988 for Congress to pass significant amendments to fair housing law. In addition to strengthening the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) enforcement powers, the Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988 added people with physical or mental disabilities and families with children to the list of groups protected from housing discrimination.

Throughout the 1990s, CBC members continued efforts to expand fair housing protections and took on new challenges to housing equality. They recognized that though minorities and other groups now were less likely to face overt discrimination, housing bias continued in new and more subtle forms such as predatory lending and reverse redlining. Caucus members led efforts to combat these practices through securing funding for fair housing enforcement programs and calling for investigations into discriminatory lending practices. Today, the Congressional Black Caucus continues working to ensure all Americans equal access to housing they can afford in the location of their choice.